NOTE: Soon after Joe Strummer’s death of an apparent heart attack on this date in 2002, I wrote about The Clash co-founder’s influence as a prophetic voice in the world of punk rock and beyond. My attempts to connect Strummer’s musicianship with Christian theology might be a stretch, but it was a fun thought experiment and I enjoyed exploring those tenuous connections on the page (or the screen). I offer it here as my tribute to Strummer, who, in my opinion, embodied the spirit of ’77 punk rock and infused it with global sounds and a politically progressive worldview that is as needed today as ever.

Earlier versions of the essay below were published in 2003 in the online Christian/emerging church publications RELEVANT and The Phantom Tollbooth.

*

Music is prophecy. Its styles and economic organization are ahead of the rest of society because it explores, much faster than material reality can, the entire range of possibilities in a given code. It makes audible the new world that will gradually become visible; it is not only the image of things, but the transcending of the everyday, the herald of the future. For this reasons, musicians, even when officially recognized, are dangerous, disturbing and subversive.

– Jacques Attali, Noise: The Political Economy of Music

Like most Midwesterners who came of age in the late 1970s, my initial exposure to punk rock came via American television newscasts of a raucous form of music coming out of England. From the safety of our living rooms, we witnessed shocking concert footage of a band that called themselves The Sex Pistols.

The Pistols were fronted by a gaunt, sneering lad named Johnny Rotten, who wore ripped shirts and safety-pinned trousers and shrieked dementedly into the microphone, proclaiming himself to be both an antichrist and an anarchist—the dual scourges of all that was holy and orderly in Western civilization. Never mind that punk in the USA originated in the clubs of New York City with bands like The New York Dolls, Ramones, Blondie, and Talking Heads. Rotten’s shocking persona captured the airwaves, and he quickly became punk’s most prominent icon. For many of us, he was the true vision, sound, and fury of punk rock—a movement that was designed to shock and unsettle, a defiance for defiance’s sake.

But there is a flipside to this image. It too is from 1977, the year UK punk first hit America’s radar. In this image, Joe Strummer, the gravel-voiced frontman of The Clash, leaps from a concert stage in Belgium to attack a 10-foot-tall barbed-wire fence. He tears at it with his bare hands, intent on destroying the wall between an inner court of fans—an “arena within an arena”—and the outer court of “less privileged” punks, the outsiders who concert security had “herded like cattle” to the margins.

Immediately a bank of security guards rushes in to pull Strummer from the wall of wire. Just as quickly, a mass of Clash fans rushes the guards and, in the true spirit of punk, anarchy ensues.

This moment, captured by a writer for the punk fanzine Zig Zag and recounted by rock critic Greil Marcus in a 1978 article, didn’t make newsreels. But it offers an alternative view of the early punk movement—an aggressive Yes to Rotten’s equally aggressive, angry No.

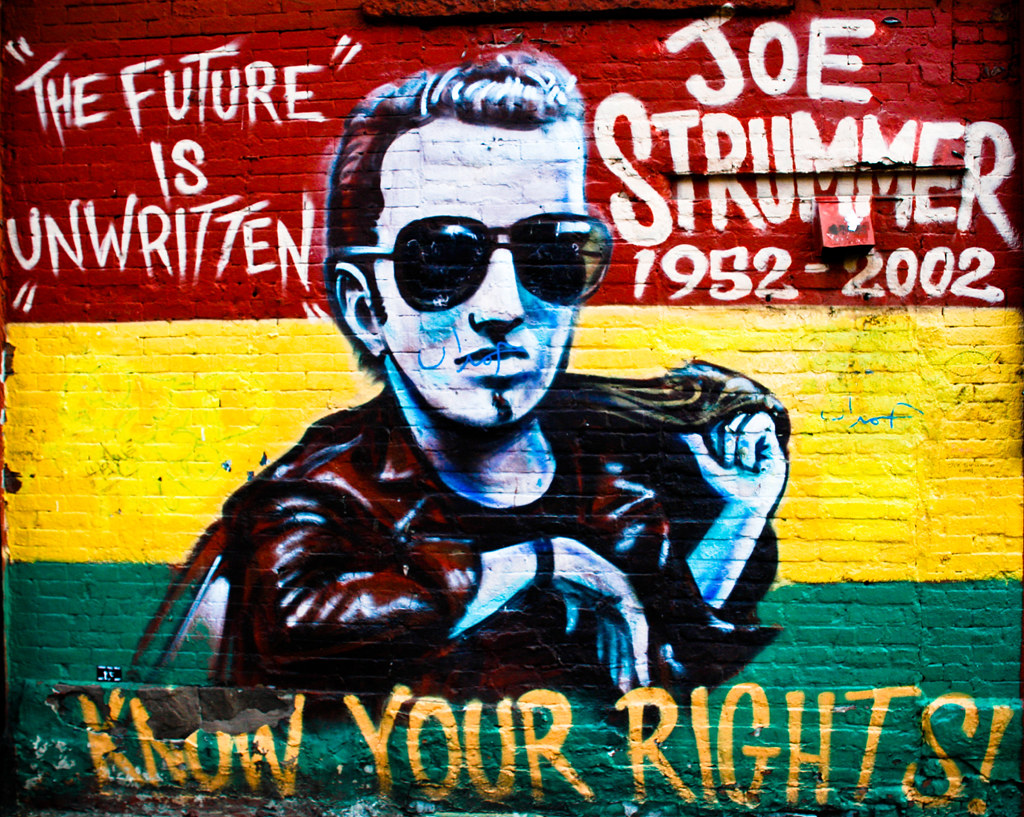

Strummer, as defiant as any punk of that era, channeled that defiance for a purpose more noble than the simple, nihilistic self-indulgence for which The Sex Pistols were known. Strummer, who died December 22, 2002, of an apparent heart attack, saw punk as a redemptive movement, a means to further the causes of social justice.

This same egalitarian, revolutionary spirit comes through in much of The Clash’s oeuvre. Contained within the lyrics of many Clash songs—those penned by Strummer and Clash co-founder Mick Jones, as well as cover tunes of styles ranging from reggae to rockabilly—are seeds of something larger than life. While Rotten and The Pistols celebrated a nihilistic trinity of no fun, no feelings and no future, Strummer and The Clash envisioned a movement that could tear down walls.

Parallel lines?

Joe Strummer was undoubtedly one of the most socially conscious figures of punk’s early years. Born John Graham Mellor in 1952, this son of a British diplomat turned his back on his middle-class upbringing and took to the streets, playing for spare change in London’s subways while a teen. (It was during this time that he changed his last name to Strummer.) After heading a pub rock band called The 101’ers, Strummer met up with Jones to form The Clash. The group signed a recording contract with CBS records in 1977 and soon rivaled The Sex Pistols as England’s biggest punk sensation.

CBS billed The Clash as “the only band that matters,” and the group tried hard to live up to the hype. Writing lyrics that challenged England’s social order, Strummer drew attention to the poor, the downtrodden, and the underprivileged—society’s outcasts herded into the outer court. He left it to lesser lights to write songs about love and teen angst.

Rock critic Lester Bangs tagged along with the band for their tour of England in 1977, and in his posthumous collection of essays, Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, Bangs describes the group’s sound and presence as “righteous.” That’s a word not often used to describe punk, or any form of rock and roll. But Bangs saw something “unpretentiously moral, and something both self-affirming and life-affirming” in The Clash. Yes, Bangs wrote, the music “seethes with rage and pain,” but “it also champs at the bit of the present system of things, lunging after some glimpse of a new and better world.”

Sure, The Clash didn’t always hit on all cylinders, but at their best moments, they were prophetic in the Old Testament sense. In songs like “Clampdown,” “Death or Glory,” “Know Your Rights,” and “Washington Bullets,” they railed against fascism and racism, while “I’m So Bored With the USA,” “Lost in a Supermarket,” and “Koka Kola” took on the consumerism and commercialism of the Western world.

Messiah figure?

While he probably never considered himself a messiah figure, Strummer’s assault on that barbed-wire barrier in Belgium resonates with the atoning work of Jesus. Through his life, death, burial and resurrection, Jesus attacked a “dividing wall of hostility” (Ephesians 2:14, NIV) that was as real as any barbed-wire barricade—and even more divisive. The barrier Jesus fought against separated “non-Jewish outsiders and Jewish insiders” (see Ephesians 2:11-16, The Message). By tearing down that wall, Christ opened the way for all of humanity—not just a privileged few—to gain access to God.

Strummer was simply trying to help the masses get a better view of the show. After all, destroying the boundaries between audience and performer has become one of punk’s foundational doctrines. But his efforts were also symbolic, for in attacking that 10-foot fence, Strummer connected the rebellious, anti-establishment, anti-elitist ethos of punk with a more universal theology that underpins the Christian faith—a theology as practiced by Jesus and preached by Paul.

‘Throw out the rule book’

It’s been nearly fifty years since Strummer ripped the veil of pop culture to expose the world to the seething underground movement of punk. By the 1980s, however, many music critics had pronounced the punk movement moribund; it had been overtaken and swallowed up by the more palatable—and profitable—“new wave” sound. Five decades later, we know punk’s influence in the world of music, fashion and culture has never been greater. Punk’s influence extends far beyond your local mall’s Hot Topic store, where you can probably buy a Clash T-shirt for $20.

Punk music continues to attract a large and devout fan base. The reason, according to Lars Frederiksen of the San Francisco punk band Rancid, has much more to do with punk’s theology than its commercial success. “You throw out the rule book in punk,” Frederiksen told USA Today. “That’s the whole point. … I love punk’s cultural diversity. You can be … black or white, male or female or eunuch.” That’s close to a paraphrase of one of the Apostle Paul’s more famous passages from the New Testament (see Gal. 3:26-28). This same egalitarian message is too often ignored by major segments of institutional Christianity.

But punk, in the spirit of Joe Strummer, continues to push equality to the forefront, and that’s one reason it remains popular today.

Cover image via The Disorder of Things.