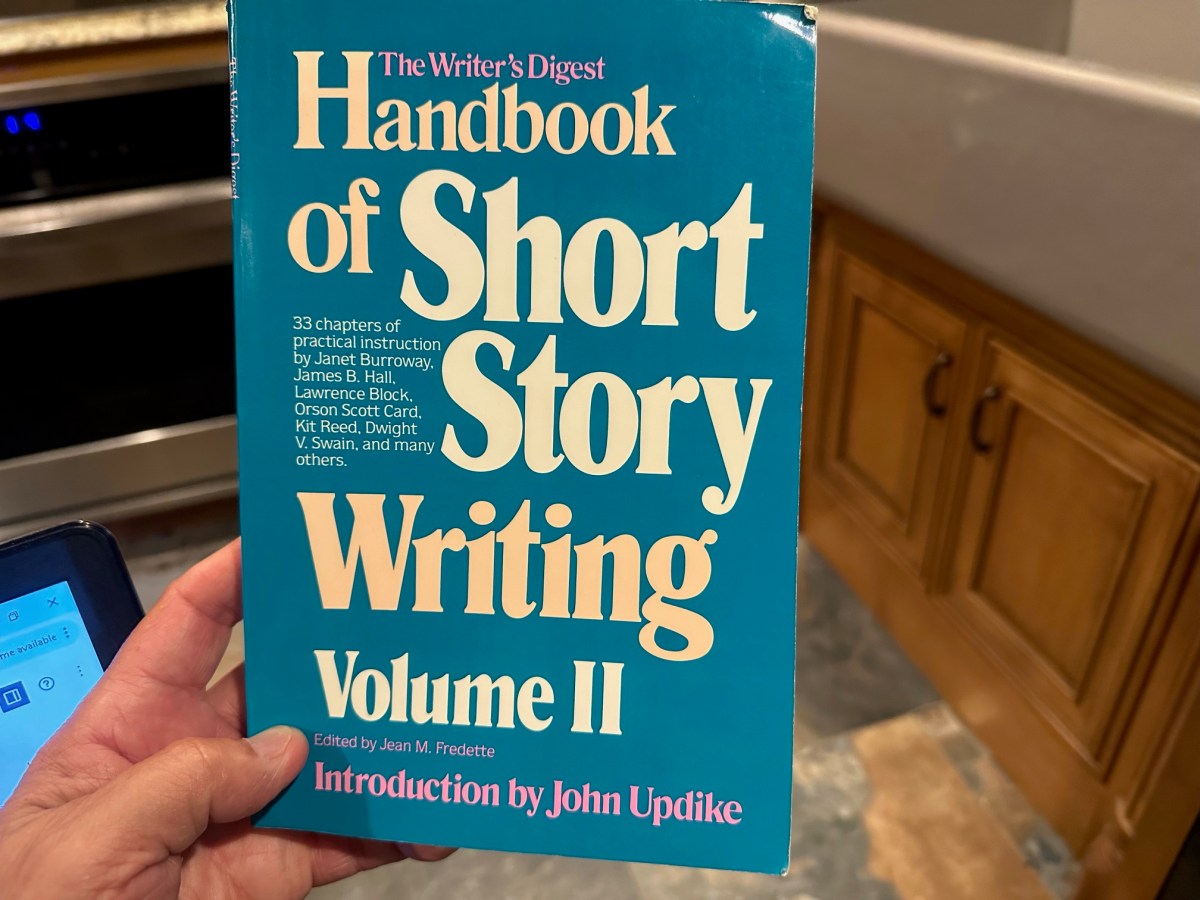

My town’s public library held a used-book sale recently, and among the armful of treasures I picked up there was The Writer’s Digest Handbook of Short Story Writing, Volume II. I’m a sucker for books about the writing craft, even if they’re nearly 40 years old (this one was published in 1988) and especially if they’re in reasonably good shape and only cost 50 cents. Shut up and take my money, I say.

This handbook’s 33 chapters cover the nuts and bolts of writing: crafting lifelike dialogue, creating a plot, the plusses and minuses of various points of view, developing the story setting, revising and editing, stuff like that. It’s all great. And most of the authors of these nuts-and-bolts essays are writers you’ve probably never heard of, which is often the case with Writer’s Digest products. But they’re all writers, notable in their own genres, and they all offer worthwhile advice.

One of the writers I had heard of: John Updike.

At one time I was quite a fan of his long and short fiction. I read all four of his “rabbit” novels — Rabbit, Run, Rabbit Redux, Rabbit Is Rich, and Rabbit at Rest — which chronicle the life of Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom. (I somehow overlooked his novella, Rabbit Remembered.) He won Pulitzer Prizes for the third and fourth books in that series. He’s also well-known in some circles for his novel The Witches of Eastwick, which became a hit movie. Of more interest to me, though, was his prolific short-story writing for The New Yorker and other magazines. His realist style and depictions of the white, Protestant, suburban middle class of the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s — a category that now seems to have faded into history — helped shape my own approach to fiction writing in my younger days. As I still identify as a realist in terms of my fiction writing, I suppose Updike’s imprint on my psyche has stuck. But not everyone was a fan of Updike. A 1997 David Foster Wallace trashing of an Updike novel called him the “chronicler and voice of probably the single most self-absorbed generation since Louis XIV.”

I write all of that about Updike under the assumption that, for younger readers of this blog, his name may not be familiar. Updike is no longer a well-known or much-discussed literary figure. But in his era, he was one of the greats.

Which brings me back to that half-dollar purchase from the library used-book sale. Updike wrote the book’s introductory chapter, “The Importance of Fiction.” In it, in his Updikean way, he stresses that fiction is “nothing less than the subtlest instrument for self-examination and self-display that mankind has invented yet.”

Pretty strong words, especially when you consider how he opens that chapter:

Well, when the importance of something has to be proclaimed, it can’t be all that important. And certainly most of the people in the United States get along without reading fiction, and more and more of the magazines get along without printing it.

It’s true that most Americans seem to manage life without reading much fiction. Iwonder what Updike would have thought about today’s attention-deficit social media landscape. As for magazines? They barely exist anymore.

Nevertheless. Fiction, he writes, is more important than psychology, sociology, history, or any of the other social sciences and humanities when it comes to examining the self. Nothing beats it. “It makes sociology look priggish, history problematic, the film media two-dimensional, and the National Enquirer as silly as last week’s cereal box.”

The question, “Does fiction matter?” has been taken on by many writers, and even researchers. A 2013 study, much cited in its day, revealed that reading literary fiction increases empathy. The psychologists who conducted the study emphasize only literary fiction — like Updike’s stuff and the classics, etc. — increased empathy. So set aside your guilty-pleasure trash and slasher reads once i a while and curl up with a classic. Because, “In literary fiction,” said one of the researchers, “the incompleteness of the characters turns your mind to trying to understand the minds of others.”

So, score one for science. But what about some other reasons fiction might matter? I spent some time in the online rabbit hole and found a few other takes worth sharing:

- Stories change us. Brad Meltzer, who writes thrillers, notes that fiction must matter. Otherwise, why would so many people try to ban books? “Stories educate us, terrify us, and even protect us,” he writes. “Jay Gatsby was the one who warned us of the dangers of our own excesses during the 1920s. Superman swooped to the rescue and gave America hope during the terrifying early days of World War II. Scout and Atticus showed us our racism, but also showed us the people who we aspire to be — who we want to be — and who we can be. And even today, it’s Harry Potter who reminds generations of young and old that magic still exists. And that’s why books get banned. That’s why they ban Maya Angelou and Judy Blume and Mark Twain. Because stories change us.”

- Fiction encourages reading. Fiction is “a gateway drug to reading,” says Neil Gaiman. “The drive to know what happens next, to want to turn the page, the need to keep going, even if it’s hard, because someone’s in trouble and you have to know how it’s all going to end … that’s a very real drive. And it forces you to learn new words, to think new thoughts, to keep going. To discover that reading per se is pleasurable. Once you learn that, you’re on the road to reading everything. And reading is key.

- Fiction is liberating. In a Leader for Good post titled “Why Fiction Is Important to Humanity and Good for You,” the author, Louise, shares several reasons to support her title argument. Among them: “[R]eading fiction is important because it can liberate you from inauthentic aspects of your life. And since we can’t change ourselves without changing what we interact with, in so doing, it also changes the world.”

- Fiction keeps stories alive. In this lengthy video from the Library of Congress’s 2023 Book Festival, writer Jesmyn Ward speaks about how she learned the history of her native Black south through the stories of her grandmother, long before she read about them through the works of Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston, and James Baldwin. She sees it as her calling to keep the stories alive through her writing (video transcript). Another writer, David Means, explains he writes fiction because “in some cases a voice that needs to say what it says or else (and I feel this, really, I do) it’ll be lost forever to the void, the same place where most stories go, forever; the real stories of men and women who lived lives — quiet desperation! — and then died, gone forever into eternity, so to speak.”

Perhaps none of us will reach the literary acclaim of John Updike, Jesmyn Ward, David Means, or Neil Gaiman. But if we are writing stories — if we are creating tales to keep alive the humanity of our selves and our histories or our fantasies — then we are doing work that matters.

Cover image: The Writer’s Digest Handbook of Short Story Writing, Volume II. Photo by me.

A long time ago in New York City, someone gave me first editions of two Updike poetry volumes, “The Carpentered Hen” and “Telephone Poles.” Your terrific blog post inspired me to revisit them–thank you!

I too need to revisit Updike. I’m not sure how well his short stories hold up these days but maybe the poetry would still feel contemporary. I think his poetry or prose would be worth reading with fresh eyes.

P.S. – I tend to forget that Updike was a decent poet, too.